Aid to Ukraine Explained in Six Charts

Photo: SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP/Getty Images

U.S. aid to Ukraine totals $68 billion, and the White House has just asked Congress for another $37.7 billion. In the spring, the new Congress will consider aid in the context of the administration’s proposed FY 2024 budget. With these decisions ahead, it is worth reviewing how much aid there has been, what that aid does, and what the administration is requesting. Such a review turns up some surprises and will help clarify discussions about future aid packages.

Q1: How much aid has there been?

A1: Congress has passed three aid packages. The first in March ($13.6 billion) was tacked onto the massive $1.5 trillion omnibus appropriations for FY 2022. The package in May ($40 billion), which contained the major portion of the aid, was a standalone bill. The package in September ($13.7 billion) was attached to the continuing resolution. It was designed to provide aid through December, when Congress will consider full-year appropriation bills. As the chart below shows, the three packages total $68 billion.

On November 15, the administration submitted a new aid request of $37.7 billion which, if passed, would bring the total to $105.5 billion. This new aid package is designed to last through the end of the fiscal year (September 30, 2023). However, at the current rate of spending ($6.8 billion per month), this would last until about May. At that point, unless the war has ended or settled into a stalemate, the administration would need to ask for additional money.

Confusion sometimes arises because the way the administration periodically announces aid packages, for example, the language from a November 4 press release: “Defense Department announced approximately $400 million in additional security assistance for Ukraine under the Ukraine security assistance initiative.” These announcements are useful for understanding how the administration is translating the pools of money appropriated by Congress into specific actions. However, these packages do not change the total amount of aid provided by Congress. Rather, they describe how the administration is using the money.

Q2: What is the aid for?

A2: The aid covers dozens of individual items, but these can be grouped into four general categories:

- Military aid (discussed separately below);

- Humanitarian assistance (discussed separately below);

- Economic support to the Ukrainian government, which goes directly to the Ukrainian government to allow continuing operations since the war has disrupted its own mechanisms for raising revenue; and

- U.S. government operations and domestic costs related to Ukraine, which covers the increased expenses to government agencies for operations like moving embassy personnel and prosecuting war criminals. It also includes $2 billion for support to energy companies, particularly the nuclear industry, to offset higher supplier costs. Some observers might exclude the energy subsidy as only tangentially related to the war in Ukraine. This tabulation includes the item since the administration categorized it as Ukraine related.

Q3: What is in the military aid to Ukraine?

A3: Military aid in the three congressionally enacted packages consists of four elements.

- Short-Term Military Support ($17 billion): This includes the transfer of weapons, both U.S. weapons and those purchased from allies, training of Ukrainian military personnel, and intelligence sharing. Much of this funding flows through the Ukrainian Security Assistance Initiative (USAI), which acts as a transfer account. Technically, the appropriations cover only the backfill equipment sent to Ukraine, not the equipment itself, but the two have been closely aligned.

- Long-Term Military Support ($10.4 billion): This consists of money that Ukraine can use to buy new weapons, mostly from the United States but also elsewhere. The problem is that these need to be manufactured, so there is a long delay. As a result, this likely funds postwar rebuilding the Ukrainian military, not current operations. (Because the USIA funds both long term and short-term support, the split is an estimate.) Confusion sometimes arises because DOD announcements state that United States has “committed” certain amounts of military equipment to Ukraine― for example, a recent fact sheet stated that “in total, the United States has committed more than $18.5 billion in security assistance to Ukraine since the beginning of the Biden Administration.” This combines the short-term and long-term support.

- U.S. Military Operations ($9.6 billion): In the spring, the United States sent about 18,000 troops to Europe to strengthen defenses and deter Russia. These deployments cost money above what was planned in the DOD budget.

- DOD General Support ($1.2 billion): This covers a wide variety of activities, some only tangentially related to Ukraine, to prepare DOD for future conflicts.

Q4: How long will it take to spend the $68 billion that has been enacted?

A4: The short answer: a long time.

Congress appropriates money, called budget authority, and then the executive branch spends the money, called outlays. That can happen relatively quickly as in the case of funding for personnel where money goes into paychecks that get cashed most immediately. Money for operations also gets spent relatively quickly as the agency, whether DOD for military operations or U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) for humanitarian relief, buys supplies and transportation for immediate use.

However, procurement funds for equipment take many years to spend out because the government pays the supplier incrementally as work is done. For the kinds of equipment being procured to support Ukraine, it takes about a year to get onto contract, then two more years before the first item is delivered and another year or more for the remaining items to be delivered. That means that money Congress appropriates in year one does not get fully spent until year five.

Some items, for example incentives for mining of rare earths, may take even longer to spend out because the process of establishing a mine is so lengthy.

Congress requires the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to “score” every bill that Congress votes on. Scoring means calculating the budget effects, both budget authority and outlays. This chart combines the CBO outlay estimates for the March, May, and September packages. Note that about $10 billion of the $68 billion will not be spent until after FY 2026. (Estimates for the latest $37.7 billion package are not yet available.)

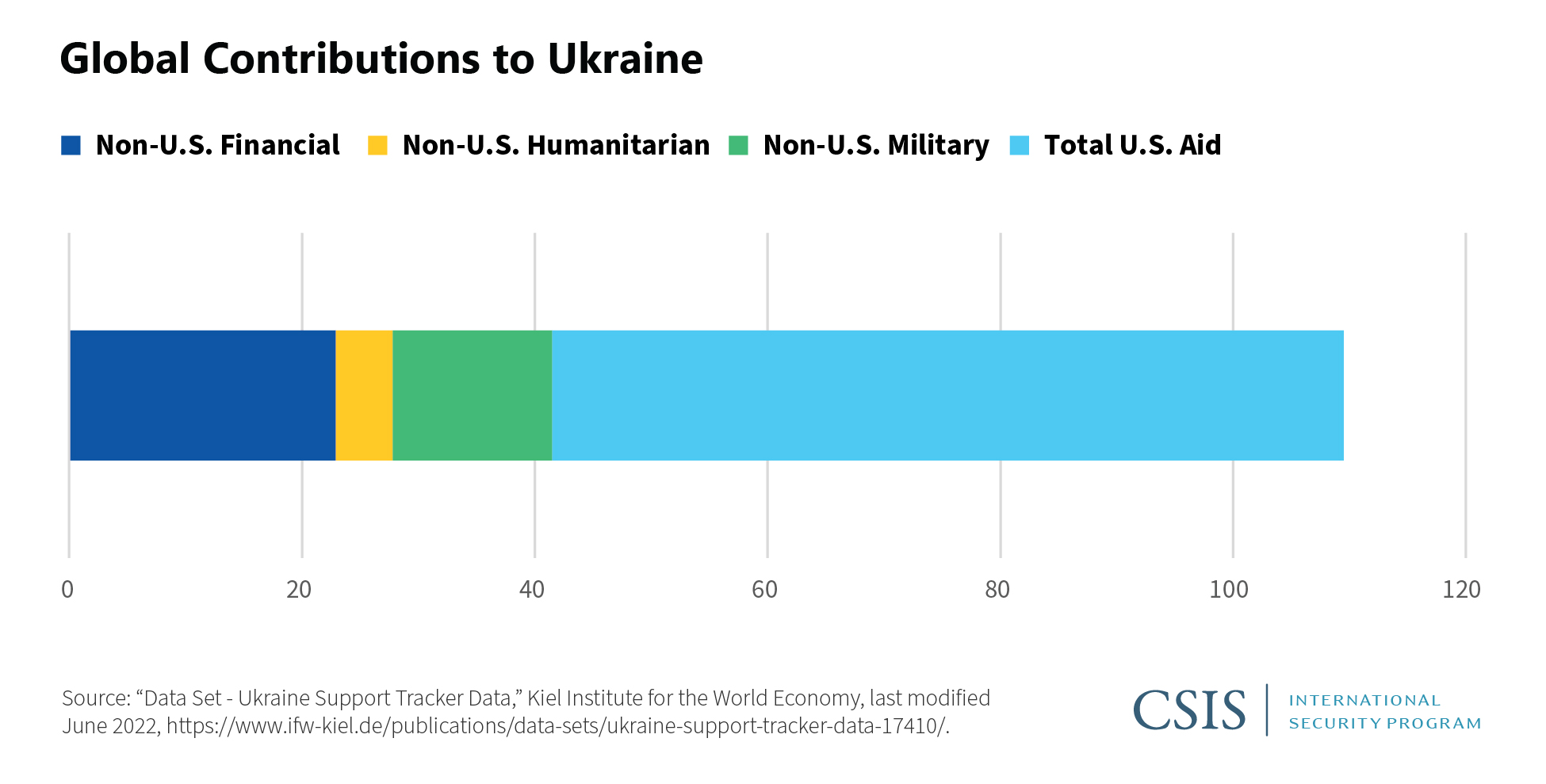

Q5: What is the rest of the world doing?

A5: To coordinate aid to Ukraine, the United States has convened the Ukrainian defense contact group consisting of over 50 countries. As tracked by Germany’s Kiel Institute, aid from non-U.S. sources is substantial ($41.4 billion). The total is likely slightly higher as some countries provide aid quietly, so their numbers do not appear here. Further, many European countries have taken in Ukrainian refugees, a burden that only partly appears in these numbers. Nevertheless, the United States provides the bulk of total aid to Ukraine—62 percent, according to the published figures.

The United Kingdom and Poland provide substantial military support. The European Union and Canada provide relatively more financial and humanitarian aid. Some countries, like Poland and the Baltic countries, provide a high level of aid compared to their economies (up to 1 percent). Others, like France and Germany, lag.

In general, the United States has provided relatively more military and financial support with other countries providing more humanitarian support. Many countries likely find humanitarian support politically easier to justify since it does not require them to take sides in the conflict.

Q6: What should Congress do going forward?

A6: Some members of Congress, particularly on the populist right and progressive left, have raised questions about the aid. The May package, the only one Congress voted on as standalone legislation, passed 368–57 in the House and 86–11 in the Senate. Although that reflects a strong bipartisan consensus, it also reveals some opposition. That opposition may increase as sentiment for negotiations to end the war increases in the United States and abroad.

Congress should not put itself in a position where it undercuts the ongoing and successful Ukrainian resistance, which depends on U.S. military support. Rather than hacking away at the aid arbitrarily, members of Congress with concerns and questions should hold hearings to ascertain more clearly what is in the aid packages and what they do. Such inquiries would allow Congress to make better-informed decisions. Most items would likely get wide support. However, some items might be questionable, some might be deferred to the regular appropriations process because of their long-term nature, and some might require increased oversight.

Mark F. Cancian is a retired Marine colonel and senior adviser with the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Critical Questions is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2022 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.